Bank of England Trials

The Search for the Inimitable Note

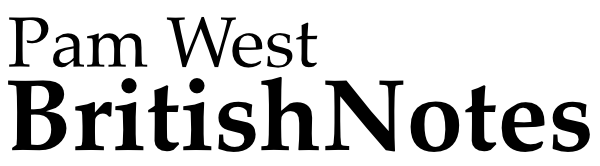

The Bank of England began the search for an inimitable banknote not long after its first issue in 1694. The earliest issues were on plain paper and soon after on watermarked paper. Printed with black ink only on white paper, they were easily forged. A majority of the general public were illiterate and easily fooled by printed specie (banknote). The basic style of the white note remained the same until its demise in 1956.

Britannia had been chosen as the Bank’s seal upon its foundation in 1694. It appeared on their banknotes in a similar design to that of John Roettier’s design for the 1672 half penny. The Bank’s early engravings of Britannia were quite basic. A new engraver was appointed in 1702 to refine Britannia and by 1797 a foliated cartouche topped by a crown encapsulated her. However, her Olive Branch soon resembled a branch of honesty and her pile of money became a beehive.

Interestingly, the Bank sought the advice of a young man imprisoned in Newcastle for altering a banknote in 1722. He suggested to the Bank that it would be harder to alter if the value appeared on the back ‘in figures against the figures on the front’. The Bank ignored this advice and took almost 100 years to take seriously this suggestion!

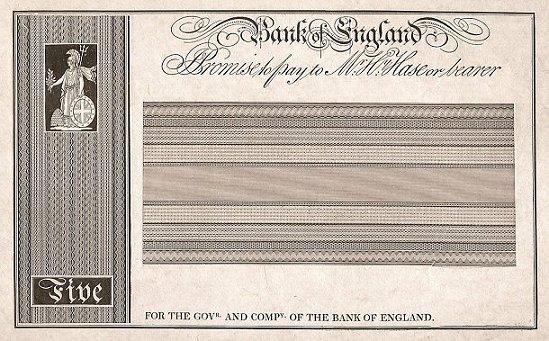

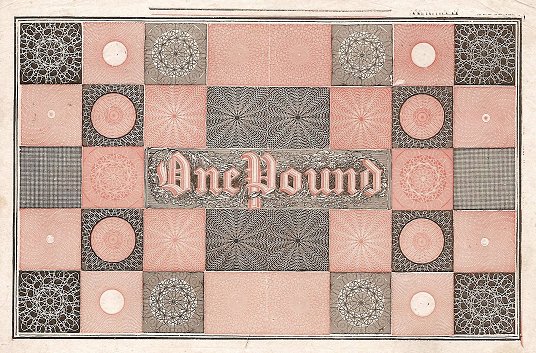

Bank of England Trial

The Bank made it known, by consulting artists, scientists and the eminent people of the day that they were seeking suggestions for banknotes that would be inimitable. In 1797 Alexander Tilloch, a London printer and publisher, submitted a design, which looked like a skewed patchwork quilt. He maintained that he was promoting the technique of crosshatching by surface printing from a block and suggested that it could not be copied by copper plate. Although he had many supporters for his proposal, the Bank’s engraver, Garnet Terry, succeeded in copying it to the Bank’s satisfaction. Tilloch continued to work on his proposal and even re-submitted it, some 20 years later.

In 1802 the Bank appointed a special committee ‘to examine Plans for the improvement of Bank Notes’. Letter press was suggested and the introduction of typography and engraving by Thomas Chapman of Fleet Street, similar to Tilloch’s design was proposed. However, Terry copied the plan and although Terry’s work was shown to the Bank almost a year later, it was deemed that a rough imitation might, effectively, fool the general public.

The Bank had a monopoly (by an Act of Parliament) on the waved line watermark paper from 1801. The Bank’s engraver, Terry was sent to Portals, their paper makers to discuss the possible use of coloured paper. All suggestions were reviewed, including alternative watermarks and by 1803 the use of coloured paper had been discounted. It was decided at this point to ‘keep the Engraving as nearly resembling the present’.

Although between 1802 and 1809 some thirty-seven ideas were considered, none were deemed suitable. Serious attention was paid to some methods previously dismissed, such as a proposal in 1807 for engravings on wood with one side printed in black, the other ‘exactly corresponding therewith, in red’.

In 1801 forgeries amounting to over £15,500 were discovered. Over half of them for the one pound and two pounds, the balance being five pounds. At this time denominations also existed for £10, £15, £20, £25, £30, £40, £50, £60, £70, £80, £90, £100, £200, £300, £400, £500 and £1,000 – forgeries of the higher denominations was extremely rare. By 1817 the sum of forgeries amounted to over £37,000. The Bank’s total note issue was over £28million. However, the toll in human life was unerring. Between 1797 and 1818 there were almost a thousand prosecutions relating to the forgery of Bank of England notes, of these 313 perpetrators were hung and 834 convicted – many of them transported to Australia. The Public were very distressed by their vulnerability and inability to read notes, let alone ascertain their authenticity. Not all those convicted had actually forged the notes, merely uttered (passed) them.

In the latter part of 1817 and the early part of 1818 the Bank’s committee was approached by an engineer, Augustus Applegath with a suggestion of a wood-block printing, an engraved vignette in relief and a pattern of irregular white lines cut by machine. Originally he was dismissed, but, persisted and was eventually invited, along with his working partner, Edward Cowper to appear before the committee. Applegath and Cowper suggested a general concept, which corresponded with the Bank’s perception of how inimitability, or rather, something close to it might be achieved.

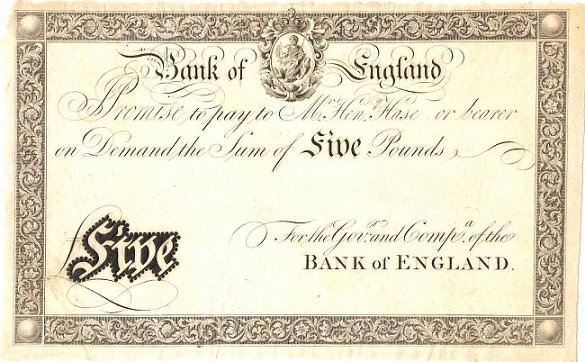

Applegath & Cowper. Two colours in registration (perfect matching front and back).

As far as the Bank was concerned this inimitability had two aspects, firstly, they should be familiar to the General Public, which meant they would be able to recognise a genuine note easily and secondly, it should be technologically advanced enough to deter the most determined forger.

Applegath and Cowper had, at the time, few specific designs. Their suggestions of simple impressions, which would ‘enable the public to protect themselves’, their plan to fill the reverse of the note with appropriate engraving appealed to the committee so much so that they advanced the sum of £1200 – a vast sum for the day - to enable them to pursue their experiments.

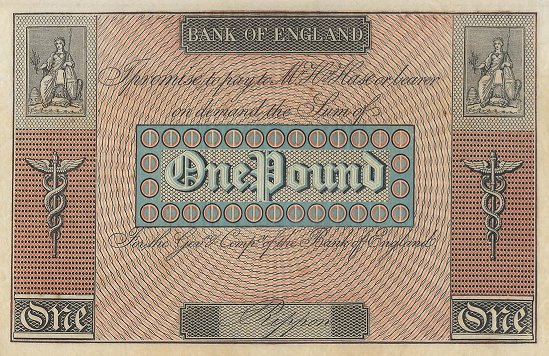

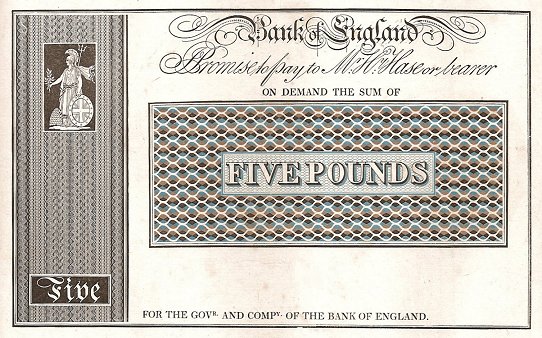

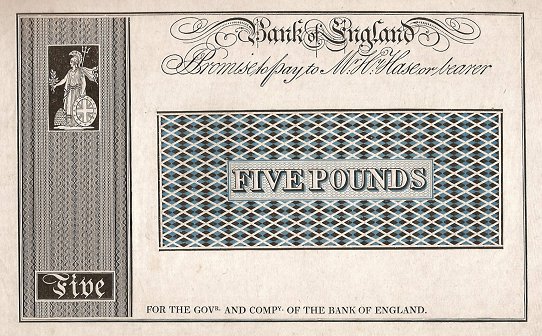

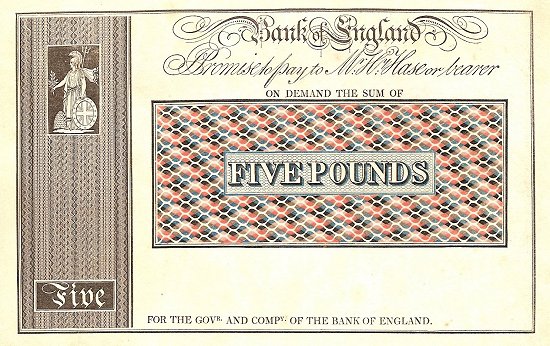

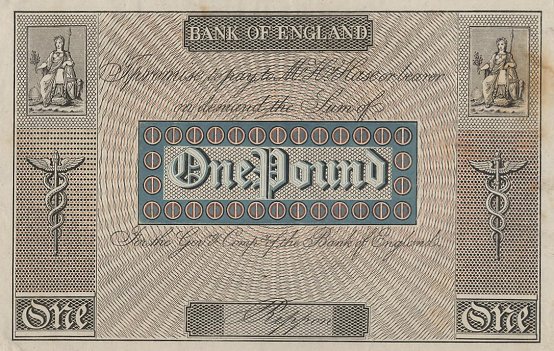

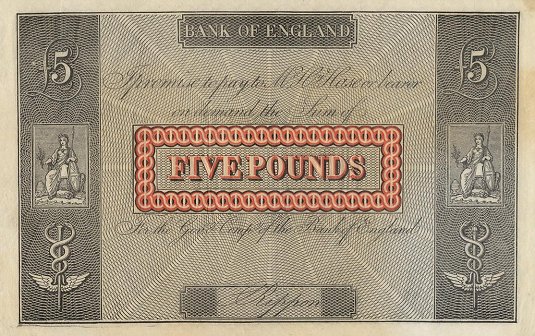

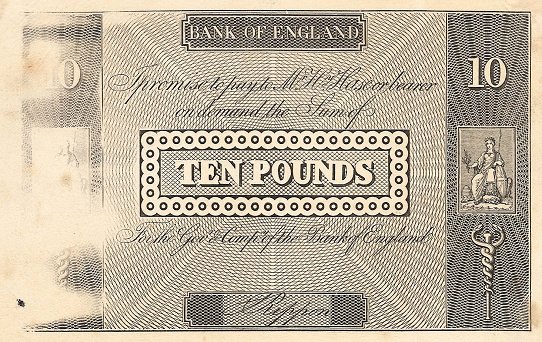

If the Bank’s engraver showed the ease of which a copy could be made, Applegath and Cowper rose to the challenge, moving towards simpler designs and adding key security features, using a simple formula to good effect. Their design consisted of Britannia on either side of the note, a large centrally-placed panel that contained the denomination in words and divided the promissory clause, all headed by ‘Bank of England’, again, in a panel. They limited their use of colour to the central panel. It was a design that they varied as the experiments progressed. Applegath and Cowper experimented with machine engraved patterns of black and red lines, and white line engraving on black and red backgrounds, utilising blocks or lines of different colours, but in perfect register – ensuring they should meet and align precisely.

Early proofs were monochrome, but later ones used as many as five colours. But, the masterstroke was that the back bore a perfect mirror image of the front. This was made possible by the adaptation of Cowper’s recent (1816) invention of a machine for printing wallpaper, which, using stereotypes bent round the cylinders. Able to print 1,200 notes per hour. Perfect registration was obtained simply by offset printing of the back of the note from a leather pad, which had already received the impression from the stereotype. The machine needed to revolve twice to print one sheet: on the first revolution no paper was inserted, and the impression was made on the leather pad; on the second, paper was fed in the front, printed, and the back set-off simultaneously, thus only requiring only one master plate.

Applegath and Cowper’s association with the Bank of four years, ended abruptly on 13th September 1821 when the Bank’s new engraver, Bawtree, satisfied the Special Committee with his copy of the partners’ latest note which had used five colours. The Bank had invested money and resources in the project. Secure accommodation for the printing process had been provided within the Threadneedle Street Bank building itself. They had even provided a steam engine to drive the partners’ machinery; also the Bank’s paper makers, Portal and Bridges had gone to the expense of installing special machinery to make paper to Applegath’s specification. Uniquely, they had been allowed to use a style of Bank of England watermarked paper, though, these proofs were printed inverted. They were paid compensation and left the Bank’s premises.

Conclusion:

A banknote produced by the human hand cannot be inimitable as it can be reproduced by another human hand.

Applegath & Cowper. Seated Britannia

Applegath & Cowper. Machine turning (Engine turning)

Applegath & Cowper. Honeycomb two colour (black & white do not count in printing as colours)

Applegath & Cowper. Diamond pattern one colour in registration

Applegath & Cowper. Honeycomb pattern four colour in registration

Applegath & Cowper. Patchwork design

Applegath & Cowper. Bi-sected circle pattern. Both Hase & Rippon printed names

Applegath & Cowper. Spiral pattern £5 in registration

Applegath & Cowper. Only known copy of a £10 Trial

The Bank received many design suggestions.

Alexander Tilloch submitted a second design in 1818.

TC. Hansard submitted a typographic design – this was reproduced in the Society of Art’s Mode of Prevention of Forgery as was RH. Solly’s Minerva Head encircled by a wreath of oak, engraved by Charles Warren.

George Cruikshank produced a ‘Bank Restriction Note’ due to Public outcry, featuring the ‘Old Lady’ eating babies – her public and ships exporting the unfortunate ‘utterer’ The rope acts as a the signature of Jack Ketch, the hangman of the day. The note was sold for 6d.